Author and Page information

- This page: https://www.globalissues.org/article/590/corruption.

- To print all information (e.g. expanded side notes, shows alternative links), use the print version:

Corruption is both a major cause and a result of poverty around the world. It occurs at all levels of society, from local and national governments, civil society, judiciary functions, large and small businesses, military and other services and so on.

Corruption affects the poorest the most, in rich or poor nations, though all elements of society are affected in some way as corruption undermines political development, democracy, economic development, the environment, people’s health and more.

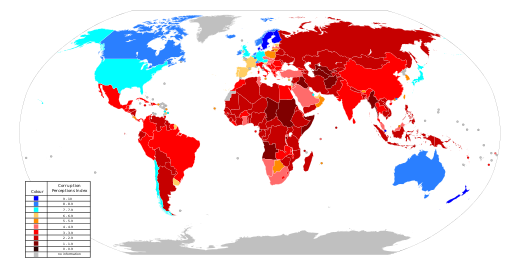

Around the world, the perception of corruption in public places is very high:

But it isn’t just in governments that corruption is found; it can permeate through society.

The issue of corruption is very much inter-related with other issues. At a global level, the international

(Washington Consensus-influenced) economic system that has shaped the current form of globalization in the past decades requires further scrutiny for it has also created conditions whereby corruption can flourish and exacerbate the conditions of people around the world who already have little say about their own destiny. At a national level, people’s effective participation and representation in society can be undermined by corruption, while at local levels, corruption can make day to day lives more painful for all affected.

A difficult thing to measure or compare, however, is the impact of corruption on poverty versus the effects of inequalities that are structured into law, such as unequal trade agreements, structural adjustment policies, so-called free

trade agreements and so on. It is easier to see corruption. It is harder to see these other more formal, even legal forms of corruption.

It is easy to assume that these are not even issues because they are part of the laws and institutions that govern national and international communities and many of us will be accustomed to it—it is how it works, so to speak. Those deeper aspects are discussed in other parts of this web site’s section on trade, economy, & related issues.

That is not to belittle the issue of corruption, however, for its impacts are enormous too.

Globalization, Multinational Corporations, and Corruption

Corruption scandals that sometimes make headline news in Western media can often be worse in developing countries. This is especially the case (as the previous link argues) when it is multinational companies going into poorer countries to do business. The international business environment, encouraged by a form of globalization that is heavily influenced by the wealthier and more powerful countries in the world makes it easier for multinationals to make profit and even for a few countries to benefit. However, some policies behind globalization appear to encourage and exacerbate corruption as accountability of governments and companies have been reduced along the way. For example,

For multinationals, bribery enables companies to gain contracts (particularly for public works and military equipment) or concessions which they would not otherwise have won, or to do so on more favorable terms. Every year, Western businesses pay huge amounts of money in bribes to win friends, influence and contracts. These bribes are conservatively estimated to run to US$80 billion a year—roughly the amount that the UN believes is needed to eradicate global poverty.

Dr Hawley also lists a number of impacts that multinationals’ corrupt practices have on the South

(another term for Third World, or developing countries), including:

- They undermine development and exacerbate inequality and poverty.

- They disadvantage smaller domestic firms.

- They transfer money that could be put towards poverty eradication into the hands of the rich.

- They distort decision-making in favor of projects that benefit the few rather than the many.

- They also

- Increase debt;

- Benefit the company, not the country;

- Bypass local democratic processes;

- Damage the environment;

- Circumvent legislation; and

- Promote weapons sales.

(See the previous report for detailed explanation on all these aspects.)

IMF and World Bank Policies that Encourage Corruption

At a deeper level are the policies that form the backbone to globalization. These policies are often prescribed by international institutions such as the World Bank and IMF. For years, they have received sharp criticism for exacerbating poverty through policies such as Structural Adjustment, rapid deregulation and opening barriers to trade before poorer countries are economic ready to do so. This has also created situations ripe for corruption to flourish:

As Western governments and the World Bank and IMF shout ever more loudly about corruption, their own policies are making it worse in both North and South. Particularly at fault are deregulation, privatization, and structural adjustment policies requiring civil service reform and economic liberalization. In 1997, the World Bank asserted that:

any reform that increases the competitiveness of the economy will reduce incentives for corrupt behavior. Thus policies that lower controls on foreign trade, remove entry barriers to private industry, and privatize state firms in a way that ensure competition will all support the fight.

The Bank has so far shown no signs of taking back this view. It continues to claim that corruption can be battled through deregulation of the economy; public sector reform in areas such as customs, tax administration and civil service; strengthening of anti-corruption and audit bodies; and decentralization.

Yet the empirical evidence, much of it from the World Bank itself, suggests that, far from reducing corruption, such policies, and the manner in which they have been implemented, have in some circumstances increased it.

Jubilee Research (formerly the prominent Jubilee 2000 debt relief campaign organization) has similar criticisms, and is also worth quoting at length:

Rich country politicians and bank officials argue that because dictators like Marcos, Suharto, and Mobutu were kept in power with western arms and were given loans to squander on ill-judged and repressive schemes, that the people of those countries—who often fought valiantly against those dictators—cannot be trusted not to waste the money released by debt cancellation. This may seem confusing to people not familiar with the logic of the IMF and World Bank. In summary:

- Creditors colluded with, and gave loans to dictators they knew were corrupt and who would squander the money.

- Creditors gave military and political aid to those dictators—knowing arms might be used to suppress popular opposition

- Therefore, successor democratic governments and their supporters, who may have been victims of corruption and oppression, cannot be trusted.

To many people in the South, this seems irrational and illogical—the logic of blaming the victim. It is the logic of power rather than of integrity, and is used to benefit the rich rather than the poor in developing countries.

A similar logic argues that if the World Bank and government export credit agencies promoted inappropriate and unprofitable projects, then southern governments proved their inability to control money because they accepted the ill-advised projects in the first place. Thus, if money is released by debt cancellation, it must be controlled by agencies which promoted those failed projects.

This is the logic that says if people were stupid enough to believe cigarette advertising, then they are too stupid to take care of themselves and the

reformedcigarette companies should be put in charge of their health care.The same institutions who made the corrupt loans to Zaire and lent for projects in Africa that failed repeatedly are still in charge, but their role has been enhanced because of their success in pushing loans. Can we trust these institutions to suddenly only lend wisely; to not give loans when the money might be wasted?

Preventing new wasted loans and new debt crises, and ensuring that there is not another debt crisis, means that the people who pushed the loans and caused this crisis cannot be left in charge.

The creditors or loan pushers cannot be left in charge, no matter how heartfelt their protestations that they have changed. Pushers and addicts need to work together, to bring to an end the entire reckless and corrupt lending and borrowing habit.

And in terms of how lack of transparency by the international institutions contributes to so much corruption structured into the system, Hanlon and Pettifor continue in the same report as cited above:

Structural adjustment programs cover most of a country’s economic governance.

… The most striking aspect of IMF/World Bank conditionality [for aid, debt relief, etc] is that the civil servants of these institutions, the staff members, have virtual dictatorial powers to impose their whims on recipient countries. This comes about because poor countries must have IMF and World Bank programs, but staff can decline to submit programs to the boards of those institutions until the poor country accepts conditions demanded by IMF civil servants.

There is much talk of transparency and participation, but the crunch comes in final negotiations between ministers and World Bank and IMF civil servants The country manager can say to the Prime Minister,

unless you accept condition X, I will not submit this program to the board. No agreed program means a sudden halt to essential aid and no debt relief, so few ministers are prepared to hold out. Instead Prime Ministers and presidents bow to the diktat of foreign civil servants. Joseph Stiglitz also notes thatreforms often bring advantages to some groups while disadvantaging others,and one of the problems with policies agreed in secret is that a governing elite may accept an imposed policy which does not harm the elite but harms others. An example is the elimination of food subsidies.

As further detailed by Hanlon and Pettifor, Christian Aid partners (a coalition of development organizations), argued that top-down conditionality has undermined democracy by making elected governments accountable to Washington-based institutions instead of to their own people.

The potential for unaccountability and corruption therefore increases as well.

Tackling corruption

What can be done to tackle this problem?

Strengthen Democracy’s Transparency Pillar

One of the pillars of democracy is transparency; knowing what goes on in society and being able to make informed decisions should improve participation and also check unaccountability.

The above-cited report by Hanlon and Pettifor also highlights a broader way to try and tackle corruption by attempting to provide a more just, democratic and transparent process in terms of relations between donor nations and their creditors:

Campaigners from around the world, but particularly the South, have called for a more just, independent, accountable and transparent process for managing relations between sovereign debtors and their public and private creditors.

An independent process would have five goals:

- to restore some justice to a system in which international creditors play the role of plaintiff, judge and jury, in their own court of international finance.

- to introduce discipline into sovereign lending and borrowing arrangements—and thereby prevent future crises.

- to counter corruption in borrowing and lending, by introducing accountability through a free press and greater transparency to civil society in both the creditor and debtor nations.

- to strengthen local democratic institutions, by empowering them to challenge and influence elites.

- to encourage greater understanding and economic literacy among citizens, and thereby empower them to question, challenge and hold their elites to account.

Address weaknesses in the global system

Improve Government Budget Transparency

A trusted government is more likely to result in a positive political and economic environment, which is crucial for developing countries, as well as already industrialized ones.

More Information

This is a large topic in itself. Over time, more will be added, but for now you can start at the following:

- Transparency International has a Corruption Perception Index. It provides many reports, statistics and information.

- The World Bank, despite criticisms about it not looking at its own policies as being a factor, do, however have a lot about corruption. A search result on World Bank site on corruption reveals many articles.

- The Corner House is a UK-based charity that provides many articles looking at corruption, bribery and related issues.

Author and Page Information

- Created:

- Last updated: